ImageBind: One Embedding Space To Bind Them All

Published:

The proposed idea is simple - mapping six different modalities to a joint embedding space. This allows data samples from different modalities, which share the same semantic meaning, to be mapped to similar vectors (i.e., vectors that are close in the cosine similarity metric) within the embedding space. Embedding modalities using explicitly aligned training data has been proposed before. For instance, the seminal works of CLIP[1] and ALIGN[2] map images and text to a joint embedding space. AudioCLIP[3] extends CLIP by adding an audio modality, and “Everything at Once”[4] embeds audio, images, and text into a joint mapping space to leverage the audio modality in video retrieval. However, embedding six different modalities - images, text, audio, depth, thermal, and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) data - particularly those without explicitly aligned training data or even datasets where they naturally coexist (e.g., you probably wouldn’t find dataset of depth images associated with sounds) is a challenge that hasn’t been tackled before. In my opinion, this opens the door to many new applications.

| Blog post, Paper, Code, Video, Demo |

|---|

|

|---|

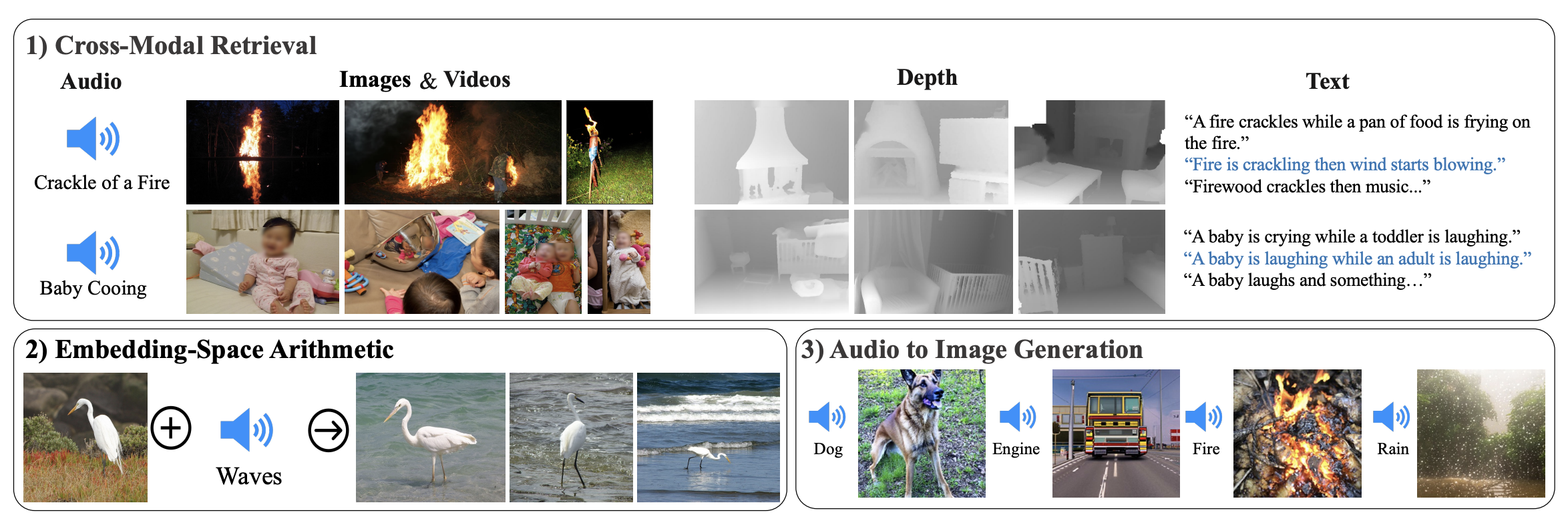

| By aligning six modalities’ embedding into a common space, IMAGEBIND enables: 1) Cross-Modal Retrieval, which shows emergent alignment of modalities such as audio, depth or text, that aren’t observed together. 2) Adding embeddings from different modalities naturally composes their semantics. And 3) Audio-toImage generation, by using ImageBind’s audio embeddings with a pre-trained DALLE-2 [] decoder designed to work with CLIP text embeddings. |

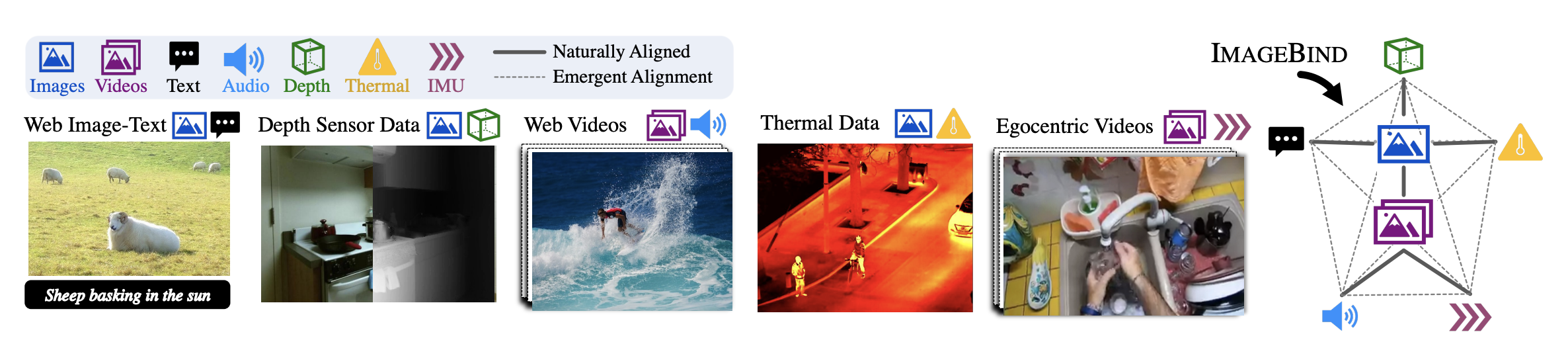

In greater detail, the authors utilize the visual modality as the common link between the modalities by aligning each modality’s embeddings to those of the images. For instance, IMU data is aligned with video using video data captured from egocentric cameras equipped with IMU. Here, the embeddings of the images and the second modality are learned using InfoNCE loss[5].

Consider a pair of modalities $(I,M)$, where $I$ represents images and $M$ represents another modality. We learn two mapping functions, $f$ and $g$, where $f$ operates on images and $g$ operates on the other modality. Given an image $I_i$ and its corresponding data sample in the other modality $M_i$ , we apply $f$ to $I_i$ and $g$ to $M_i$ to obtain the normalized embeddings $q_i = f(I_i)$ and $k_i = g(M_i)$. Both the encoders and the embeddings are learned by optimizing the InfoNCE loss[5]:

$ L_{I,M}= -\text{log}\frac{\text{exp}(q^{T}_ik_i/\tau)}{\text{exp}(q^{T}_ik_i/\tau) + \sum _{i \not= j}{\text{exp}(q^{T}_ik_j/\tau)} } $

There $\tau $ is a scalar controlling the temperature and $j$ denotes unrelated data samples in the batch, where every $j \not= i $ is considered a negative pair. Optimizing this loss makes $q_i$ and $k_i$ close in the embedding space and optimizing on a large data set thus aligns the two modalities $I$ and $M$. In practice, the symmetric loss $L = L_{I,M} + L_{M,I}$ is used.

This formulation assumes that for every modality $M$, we have a large-scale dataset with corresponding pairs $(I_i, M_i)$. This is true for text, as large-scale text-image datasets have been collected (notably by the LAION Foundation[6,7,8]), but not for the other four modalities. However, such pairings naturally arise from other existing datasets. To this end, the authors used the (video, audio) pairs from the Audioset dataset [9], the (image, depth) pairs from the SUN RGB-D dataset [10], the (image, thermal) pairs from the LLVIP dataset [11], and the (video, IMU) pairs from the Ego4D dataset [12]. Note that ImageBind optimizes using only pairs of images and samples from other modalities, i.e., pairs of the form $(I,M)$. The model is never explicitly trained to align other $(M_1, M_2)$ pairs of modalities, such as learning to align depth maps with text. However, by optimizing the two “connections” $(I, M_1)$ and $(I, M_2)$, the alignment of $M_1$ and $M_2$ naturally emerges (similar to transitivity in math), allowing the model to perform zero-shot cross-modality retrieval between any pair of modalities.

|

|---|

| Different modalities occur naturally aligned in different data sources, for instance images+text and video+audio in web data, depth or thermal information with images, IMU data in videos captured with egocentric cameras, etc. IMAGEBIND links all these modalities in a common embedding space, enabling new emergent alignments and capabilities. |

In practice, the authors do not directly use image and text datasets. Instead, for simplicity, they use the pre-trained vision and text encoders from OpenCLIP[13], which are kept frozen during training. Audio is converted into 2D mel-spectrograms, and the thermal and depth modalities are converted into single-channel images. These are then passed to ViT encoders. For the IMU data, which consists of acceleration and gyroscope measurements across the X, Y, and Z axes, five-second clips containing 2K samples are projected using 1D convolution with a kernel size of 8. Then, the entire sequence is passed to a Transformer. A linear projection head is added to each modality encoder to obtain a fixed-size, d-dimensional embedding that is normalized and used in the InfoNCE loss.

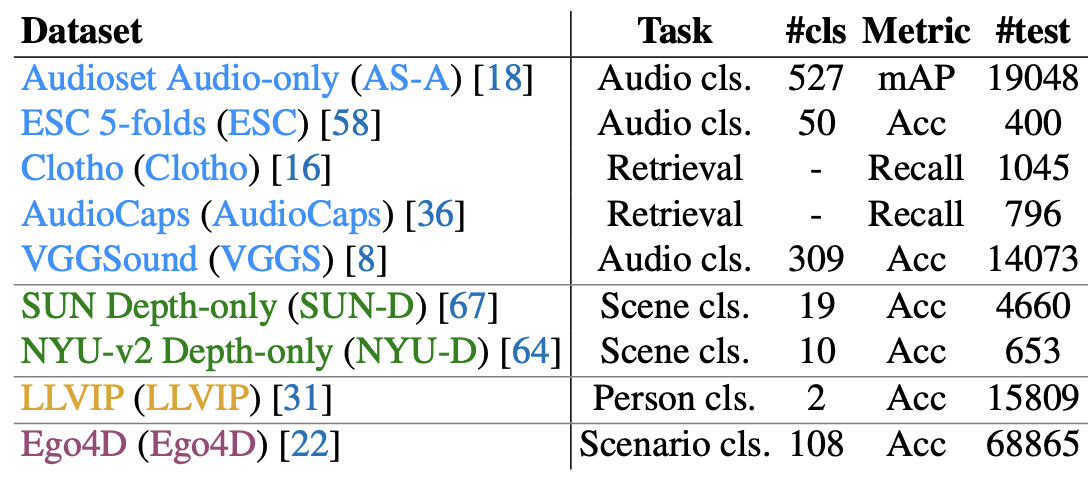

The zero-shot classification performance of the model can be evaluated using text prompts, as was originally done in CLIP[1]. For vision-related tasks, ImageBind would perform the same as Open-CLIP, since it uses the frozen text and image encoders from Open-CLIP. The four other modalities are aligned to the “language and vision” embedding space “inherited” from Open-CLIP. It’s important to note that for the other four modalities, ImageBind was never explicitly trained with (text, other modality) pairs. Thus, any text-prompt-based audio/depth/thermal/IMU zero-shot capabilities are implicitly learned by using images as an “intermediate modality”. For example, by training on (text, image) pairs and (image, audio) pairs, ImageBind learns to perform zero-shot classification on audio. The authors term this capability as “emergent zero-shot”. This is different from AudioCLIP, for example, which is explicitly trained on (text, sound) pairs and thus performs “zero-shot”, but not “emergent zero-shot” classification. I emphasize this point so we can interpret the experimental results in full context and understand that ImageBind is trained using a weaker form of supervision. The emergent zero-shot performance is evaluated on the benchmarks detailed in the table below (Table 1 in the paper). The zero-shot performance on image and video benchmarks is listed in the experiments for completeness, which is again the same as OpenCLIP’s performance.

|

|---|

| For audio, depth, thermal, and Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) modalities. The authors evaluate IMAGEBIND without training for any of these tasks and without training on paired text data for these modalities. For each dataset, we report the task (classification or retrieval), number of classes (#cls), metric for evaluation (Accuracy or mean Average Precision), and the number of test samples (#test). |

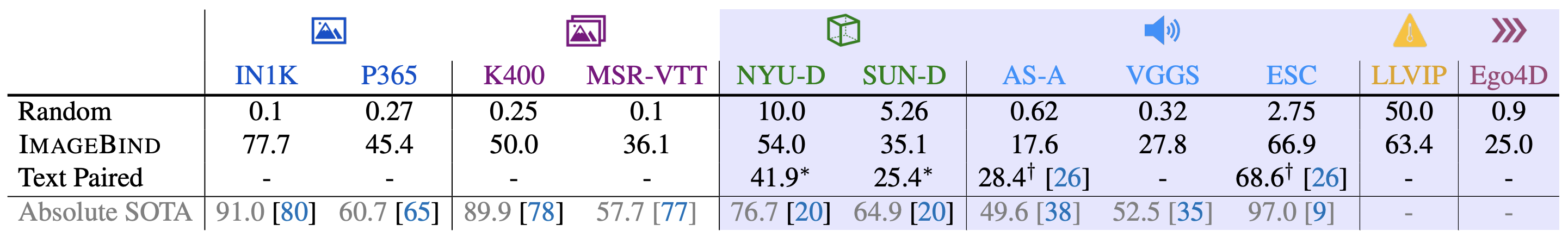

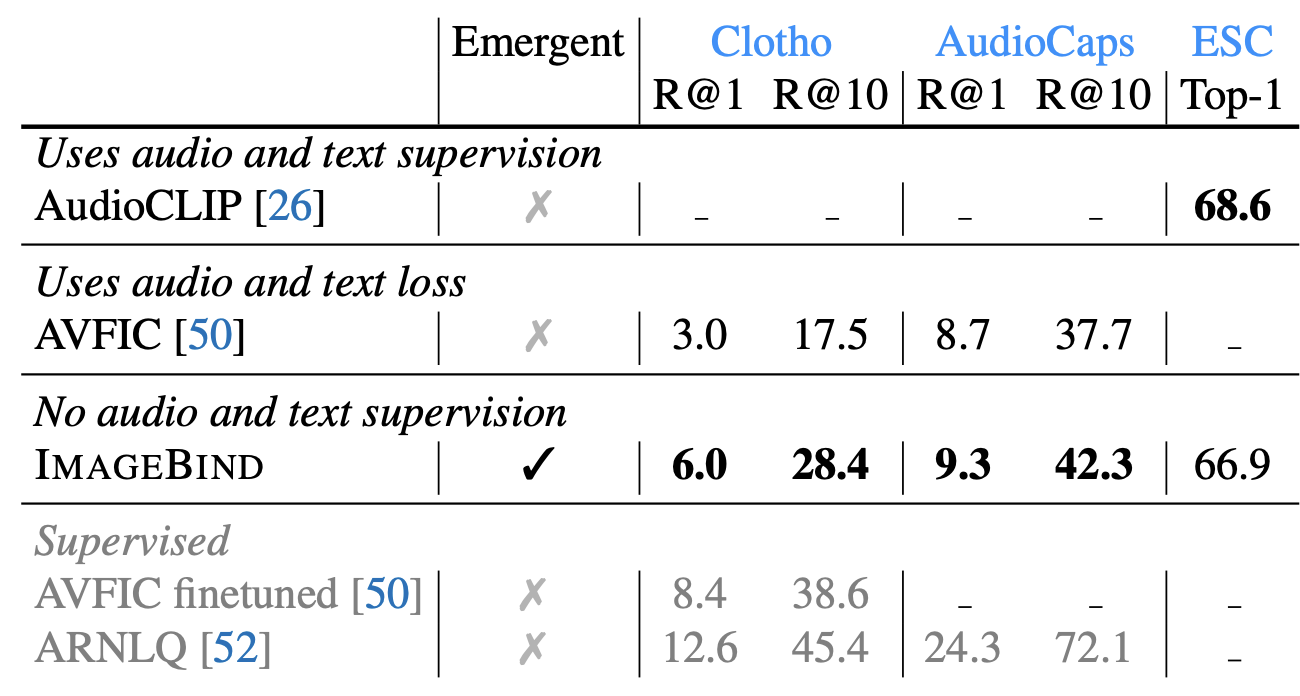

The table below (Table 2 in the paper) details the full zero-shot (blank columns) and emergent zero-shot (blue columns) performances. ImageBind’s performance is given in the second row, while the third row, labeled “Text-Paired,” refers to the performance of the best method trained using (text,

Examining the results, we can observe that the model performs significantly better than random, indicating an alignment between two disconnected modalities. Notably, although the model was never trained on (text, audio) pairs, it performed better on ESC than a model that was trained on (text, audio) pairs. ImageBind performs better than the “Text-Paired method” in the depth modality benchmarks, but in my opinion, this comparison should be taken with a grain of salt, as the “Text-Paired” method is a baseline obtained by converting the depth images to grayscale and passing them to OpenCLIP Vit-H, which likely contained very few (text, depth as grayscale) data pairs in its training dataset.

The authors further compare the emergent zero-shot audio classification and retrieval performance of ImageBind to previous methods that use text supervision. Specifically, ImageBind is compared to AudioCLIP[3] which uses (audio, text) supervision and to AVFIC [14] which uses automatically minded (audio, text) pairs. The results are listed in the table below (Table 3 in the paper). ImageBind outperforms AVFIC and achieves comparable performance to AudioCLIP without training on explicit (text, audio) supervision, demonstrating emergent zero-shot audio retrieval and classification capabilities.

The authors use MSR-VTT-1A to evaluate the text-to-audio and video retrieval capabilities of ImageBind. It’s worth noting that the methods compared against are somewhat outdated, given the fast-paced progress in AI today. More recent methods, such as CLIP2TV[15], Florence[16], and Frozen in Time[17], perform dramatically better. Interestingly, ‘Everything at Once’ [4], which embeds text, audio, and video into a joint space, is not included in the comparison. This omission is notable, in my opinion, as it represents an excellent baseline to include and discuss, given that it’s one of the few works that performs zero-shot text-to-audio+vision retrieval. Using the vision modality alone, ImageBind achieves a 36.1% recall@1, which matches OpenCLIP’s performance as it uses OpenCLIP’s text and image encoders. The inclusion of the audio modality increases this result to 36.8%.

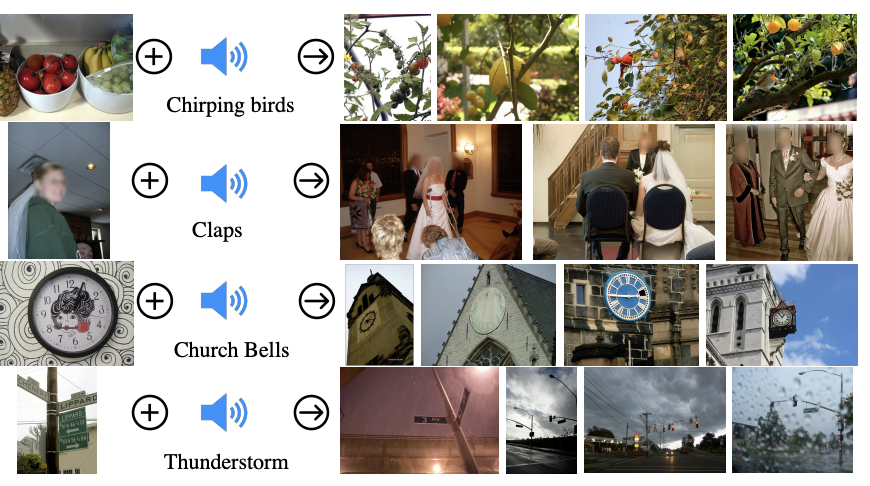

An interesting property of the learned embedding space is multimodal arithmetic. We can compose semantic information from different modalities by summing the corresponding semantic vectors. For example, adding the embedding vector of an image of fruits on a table to the embedding vector of the sound of chirping birds could result in an embedding vector that captures both semantic concepts. This might correspond to an image of a tree with fruits and birds on the branches. The figure below (Figure 4 in the paper) demonstrates some qualitative results:

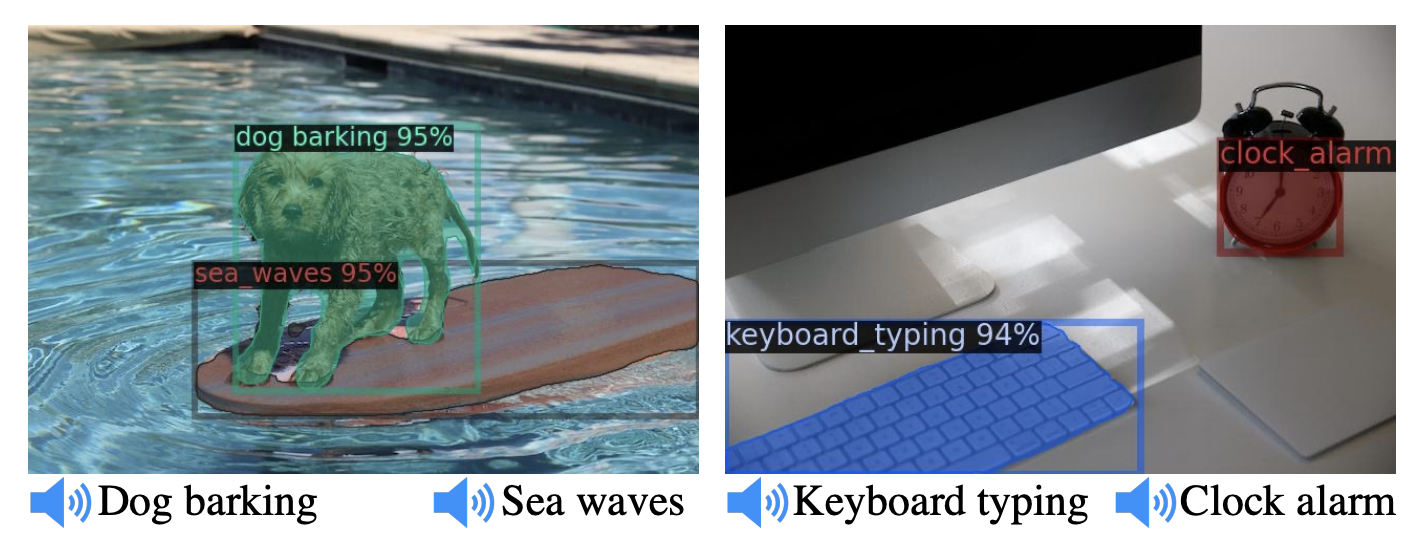

The authors also demonstrate that text prompts can be replaced by audio prompts to enable “sound-based” object detection and image generation which also qualitatively show alignment between the different modalities.

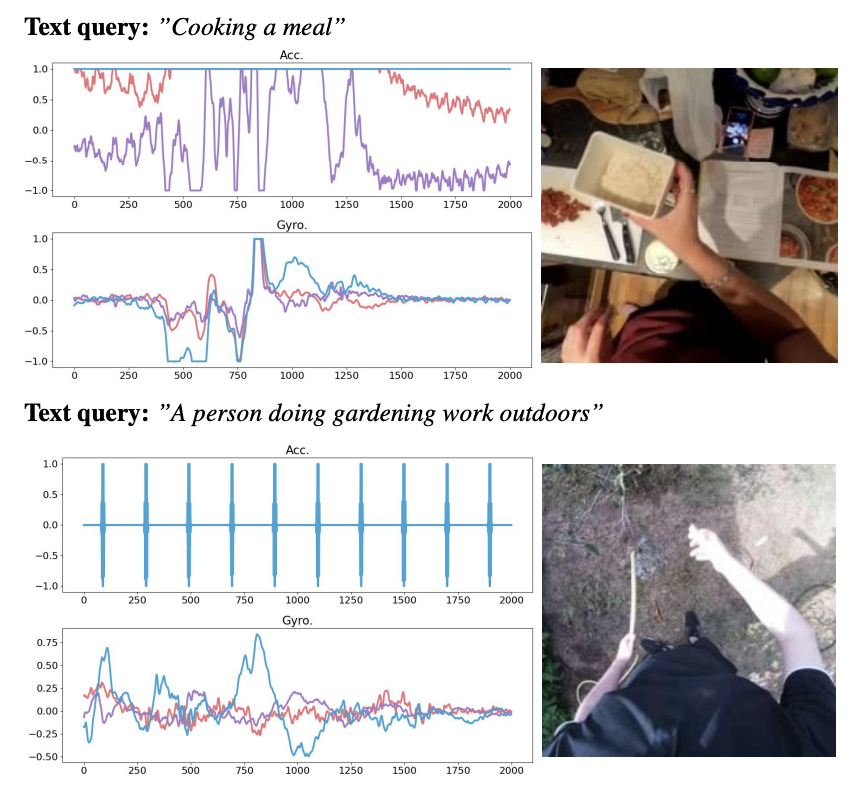

Unfortunately, the paper does not provide any qualitative results on sound-based object detection. An interesting experiment would be to use the same pipeline and dataset to measure object detection with text prompts versus audio prompts and evaluate the degradation. Additionally, the paper (and the demo) do not show qualitative results for the thermal or depth modalities. Only a few qualitative results for the IMU are provided in Figure 7 in the appendix. However, now that the model and code have been released, the community can analyze and examine the performance and limitations of ImageBind across the different modalities.

|

|---|

| IMU retrievals and corresponding video frames for a text query. |

To summarize, the paper demonstrates that cross-modality joint embedding can be learned without explicit supervision by using vision as a “binding” modality instead. The paper showcases zero-shot capabilities across modalities. However, as acknowledged by the paper, these are early results, and the model is not yet robust enough for real-world applications. Nonetheless, this research opens the door for further exploration and experimentation.

References

[1] Radford, Alec, et al. “Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021.

[2] Jia, Chao, et al. “Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021.

[3] Guzhov, Andrey, et al. “Audioclip: Extending clip to image, text and audio.” ICASSP, 2022.

[4] Shvetsova, Nina, et al. “Everything at once-multi-modal fusion transformer for video retrieval.” CVPR. 2022.

[5] Oord, Aaron van den, Yazhe Li, and Oriol Vinyals. “Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding.” NeurIPS, 2018.

[6] https://laion.ai/

[7] Schuhmann, Christoph, et al. “Laion-400m: Open dataset of clip-filtered 400 million image-text pairs.” Data Centric AI NeurIPS Workshop 2021.

[8] Schuhmann, Christoph, et al. “Laion-5b: An open large-scale dataset for training next generation image-text models.” NeurIPS 2022

[9] Gemmeke, Jort F., et al. “Audio set: An ontology and human-labeled dataset for audio events.” ICASSP, 2017.

[10] Song, Shuran, Samuel P. Lichtenberg, and Jianxiong Xiao. “Sun rgb-d: A rgb-d scene understanding benchmark suite.” CVPR. 2015.

[11] Jia, Xinyu, et al. “LLVIP: A visible-infrared paired dataset for low-light vision.” CVPR. 2021.

[12] Grauman, Kristen, et al. “Ego4d: Around the world in 3,000 hours of egocentric video.” CVPR. 2022.

[13] Gabriel Ilharco, Mitchell Wortsman, Ross Wightman, Cade Gordon, Nicholas Carlini, Rohan Taori, Achal Dave, Vaishaal Shankar, Hongseok Namkoong, John Miller, Hannaneh Hajishirzi, Ali Farhadi, and Ludwig Schmidt. Openclip, 2021, https://github.com/mlfoundations/open_clip

[14] Nagrani, Arsha, et al. “Learning audio-video modalities from image captions.” , ECCV 2022

[15] Gao, Zijian, et al. “CLIP2TV: Align, Match and Distill for Video-Text Retrieval.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.05610 (2021).

[16] Yuan, Lu, et al. “Florence: A new foundation model for computer vision.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.11432 (2021).

[17] Bain, Max, et al. “Frozen in time: A joint video and image encoder for end-to-end retrieval.” CVPR. 2021.

[18] Ramesh, Aditya, et al. “Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 (2022).